© Ali AlSaibie, PhD.

A disk drive read head can be modeled as a pair of rotating masses connected by a flexible shaft. As shown on Figure 1. represents the motor's inertia, while represents the head's inertia. The flexible shaft has a stiffness and damping coefficient . is the torque applied by the motor while is the disturbance torque.

EXERCISE 1

Using the impedance method, find the equations of motion for the system in the Laplace Domain

For the following questions, use the parameters from Table 1

Derive the transfer function symbolically.

Hint: Solve for a linear systems of equation or use Cramer's rule.

Hint: Use the following functions: numden(), sym2poly() and tf() to convert a symbolic T.F to a Laplace T.F.

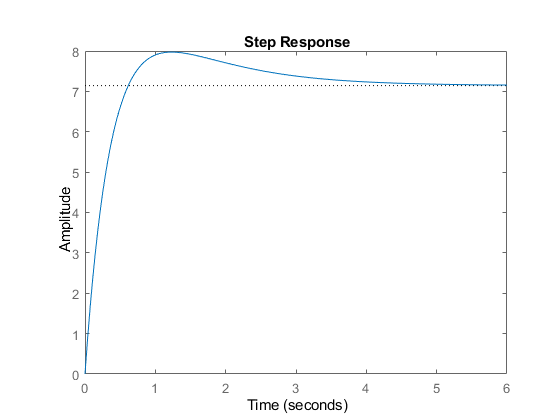

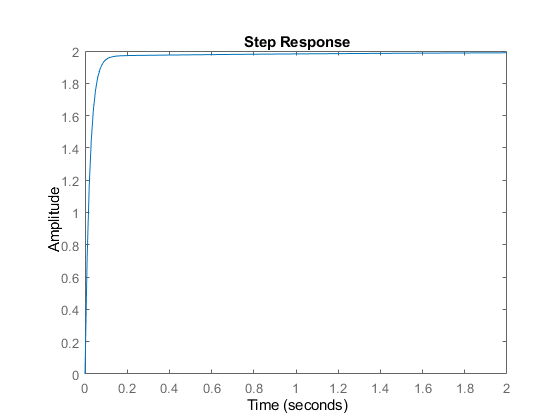

Simulate the response to a step input using the MATLAB step() command, then call the stepinfo() command on the same system to get the performance specifications of this system.

Table 1 Disk Drive Parameters

| Parameter | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0 |

clear all;

syms s K b I_h I_m

K_ = 0.07; b_ = 0.1; I_h_ = 0.04; I_m_ = 0.1;

A = [I_m*s^2+b*s+K, -b*s-K; -b*s-K, I_h*s^2+b*s+K];

B = [1; 0];

Gx = inv(A)*B;

G1s = subs(s^2*Gx(1), {K I_m I_h b}, {K_ I_m_ I_h_ b_});

G2s = subs(s^2*Gx(2), {K I_m I_h b}, {K_ I_m_ I_h_ b_});

[num,den] = numden(G1s);

num = sym2poly(num);

den = sym2poly(den);

G1 = tf(num,den);

[num,den] = numden(G2s);

num = sym2poly(num);

den = sym2poly(den);

G2 = tf(num,den);

G1

G2

figure()

step(G2)

stepinfo(G2)G1 =

200 s^2 + 500 s + 350

---------------------

20 s^2 + 70 s + 49

Continuous-time transfer function.

G2 =

500 s + 350

------------------

20 s^2 + 70 s + 49

Continuous-time transfer function.

ans =

struct with fields:

RiseTime: 0.4399

SettlingTime: 3.5359

SettlingMin: 6.4468

SettlingMax: 7.9731

Overshoot: 11.6240

Undershoot: 0

Peak: 7.9731

PeakTime: 1.2365

EXERCISE 2

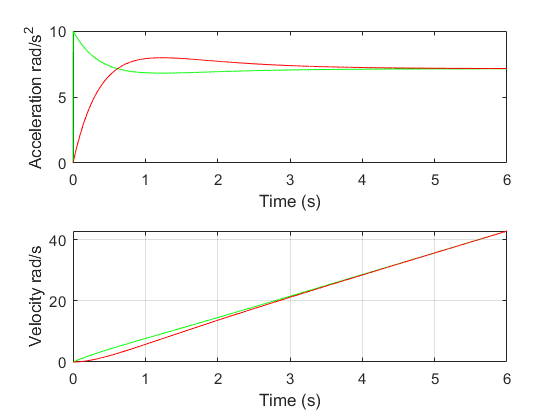

Use basic numerical integration to simulate the response of the system to a step input , note that this is a 2DOF system, so the numerical integration vector would be

But you will need to keep track of acceleration as well. So, either create a 6xn state vector to store and or keep a separate array for the accelerations.

Plot the angular accelerations on one sublot, and the angular velocities on a second subplot.

Hint: You already have the EOM from task 1, construct the numerical integration xdot function from them.

You should get the same response from step() if you specify

dxdt = @(t,x,u) [x(2);...

(u - K_ * x(1) - b_ * x(2) + K_ * x(4) + b_ * x(5)) / I_m_;...

x(5);...

(- K_ * x(4) - b_ * x(5) + K_ * x(1) + b_ * x(2)) / I_h_];

% Integration Time step

dt = 0.001;

% Time vector

t_sim = 0:dt:4;

% Initialize x

x0 = [0; 0; 0; 0; 0; 0];

x_sim = zeros(6,length(t_sim)); % Empty 6xn array

u = ones(1,length(t_sim)); % Empty 1xn vector

x_sim(:,1)= x0;

for ix = 1:length(t_sim)-1

xdot = dxdt(t_sim(ix), x_sim(:,ix), u(1,ix+1));

x_sim(1, ix+1) = x_sim(1, ix) + xdot(1) * dt;

x_sim(2, ix+1) = x_sim(2, ix) + xdot(2) * dt;

x_sim(3, ix+1) = xdot(2);

x_sim(4, ix+1) = x_sim(4, ix) + xdot(3) * dt;

x_sim(5, ix+1) = x_sim(5, ix) + xdot(4) * dt;

x_sim(6, ix+1) = xdot(4);

end

figure()

subplot(211)

plot(t_sim, x_sim(3,:), 'g'); hold on

plot(t_sim, x_sim(6,:), 'r');

xlabel('Time (s)')

ylabel('Acceleration rad/s^2');

subplot(212)

plot(t_sim, x_sim(2,:), 'g'); hold on

plot(t_sim, x_sim(5,:), 'r')

xlabel('Time (s)')

ylabel('Velocity rad/s');

grid on

EXERCISE 3

From the response in the previous task, numerically compute the following performance values for the acceleration response : Rise Time , Peak Time , Settling Time , and Percent Overshoot . And display the computed results of these performance specifications on the figure. Compare the values you obtained from stepinfo() to the values you numerically computed.

Hints:

For Rise Time: You need to compute the time it takes to go from 10% to 90% of the final output

For %OS, find the max() value in the response and compare with the final value x(end)

For Peak Time: use the index of max() to find the corresponding time.

For Settling Time: This is more involved. You need to capture the instance when the response reaches ND stays within 2% of the final value. One way to do this is to set the settling time whenever the response reaches 2% of the final value and clear it (set for instance) if the response eaves the 2% error band.

xfinal = x_sim(6,end);

[xmax,ixmax] = max(x_sim(6,:));

tp = t_sim(1,ixmax);

p_overshoot = (xmax / xfinal - 1 ) * 100;

tr0 = -1;

tr1 = -1;

ts = -1;

for ix=1:length(t_sim)

if tr0 == -1 && x_sim(6, ix) >= 0.1 * xfinal

tr0 = t_sim(1,ix);

end

if tr1 == -1 && x_sim(6,ix) >= 0.9 * xfinal

tr1 = t_sim(1,ix);

end

if ts == -1 && abs(x_sim(6,ix) - xfinal) <= 0.02 * abs(xfinal)

ts = t_sim(1,ix);

end

if ts ~= -1 && abs(x_sim(6,ix) - xfinal) > 0.02 * abs(xfinal)

ts = -1;

end

end

tr = tr1 - tr0;

stepinfo(G2)

disp(['Settling Time:' num2str(ts), ', Peak Time:' num2str(tp), ', Rise Time:' num2str(tr), ', %OS:' num2str(p_overshoot)])ans =

struct with fields:

RiseTime: 0.4399

SettlingTime: 3.5359

SettlingMin: 6.4468

SettlingMax: 7.9731

Overshoot: 11.6240

Undershoot: 0

Peak: 7.9731

PeakTime: 1.2365

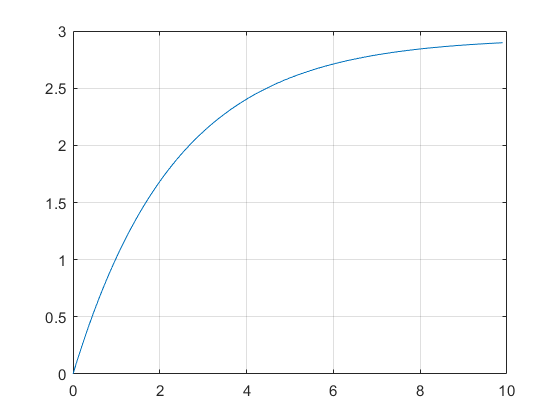

Settling Time:3.44, Peak Time:1.229, Rise Time:0.441, %OS:11.435You are given a real brushed DC Motor, but you don't have its full specifications. You do; however, have a simple model for a DC motor and you are given three sets of experimental data for a motor:

i. The angular velocity (rad/s) of the motor in response to a step voltage input of 10V

ii. The torque-speed curve for the motor at a set input voltage of 5V.

iii. The torque-speed curve for the motor at a set input voltage of 10V.

Each of the above data sets are provided in a separate and labeled csv file. The below code snippet shows you how to read the data into MATLAB arrays. Make sure the *.csv file is placed in the same folder as the MATLAB script file.

clear all

Data = csvread('Part_I_Problem_B_Data_Step_Response.csv');

t = Data(:,1);

x = Data(:,2);The Simple DC Motor transfer function is given as:

which is equivalent to , if all the constants are lumped. Note that the data set for the step response is given for angular velocity, so we need . This can be easily derived by differentiating the angular position, by multiplication with a differentiator , which gives the first order transfer function:

And remember, for the torque-speed curve, we use the time domain relationship that relate input voltage, angular velocity and torque:

EXERCISE 4

Obtain, from the step response data set, the values of and in Equation 2.

The response is first order, if you find the time constant and scale the response you can find the two values and . Hint: Apply the Final Value Theorem to find K

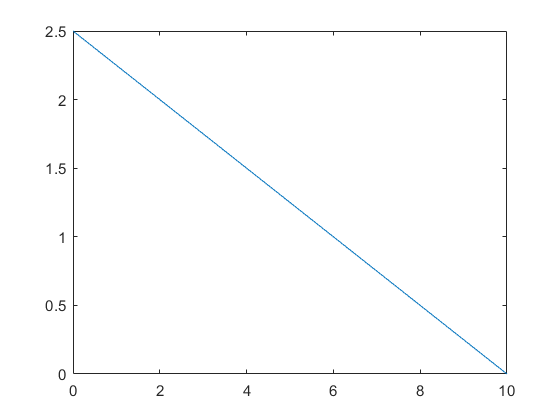

Obtain, from the two torque-speed curve data sets, the value of the coefficients in Equation 3. Use

Once plotted, you can perform this task using hand calculations, as covered in class.

From the previous two tasks, compute all the remaining coefficients, , in Equation 1

Also covered in class.

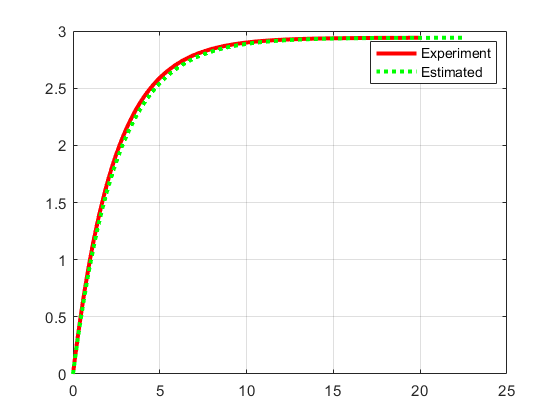

Now that you can redefine your transfer function, simulate it to a step input using the step() command and compare it to the step response data in the provided data set. (Remember to scale by 10 to account for the value of voltage input of 10V and to use the transfer function , which is equal to

figure()

plot(t(1:100),x(1:100)); grid on

ix = 1 ;

while x(ix) < 0.64 * x(end)

ix = ix + 1;

end

tau = t(ix);

a = 1 / tau

K= a * x(end) / 10;

s = tf("s");

G = K / (s + a);

Data = csvread('Part_I_Problem_B_Data_Torque_Speed_10V.csv');

w = Data(:,1);

T = Data(:,2);

figure()

grid on

plot(w, T)

e = 10;

Ra = 8

wnoload = w(end)

Tstall = T(1)

Kt = Ra * Tstall / e

Kb = e / wnoload

Jm = Kt / (Ra * K)

Dm = a*Jm - Kt*Kb/Ra

figure();

plot(t(1:200), x(1:200), 'r', 'LineWidth', 3); hold on; grid on

[xstep, tstep] = step(10*G);

plot(tstep, xstep, ':g', 'LineWidth', 3)

legend({'Experiment', 'Estimated'})a =

0.4000

Ra =

8

wnoload =

10

Tstall =

2.5000

Kt =

2

Kb =

1

Jm =

2.1250

Dm =

0.6000

This part is meant to serve as a tutorial on how to numerically implement a PID controller in a simulation. A MATLAB template script is provided to get you started. Follow through and complete the tasks.

A PID controller takes the form shown on Figure 2. Using the transfer function form, we can come up with a reduced equivalent closed-loop form and simulate the response of the feedback system to an impulse, step or ramp response directly, and this is useful in a number of control design scenarios. The reduced form is shown on Figure 3

But as we discussed in the previous assignment, implementing the simulation using numerical integration is a much more flexible design platform. Let's first get a sense on how to implement the PID Controller using transfer functions and using the reduced closed-loop form.

EXERCISE 5

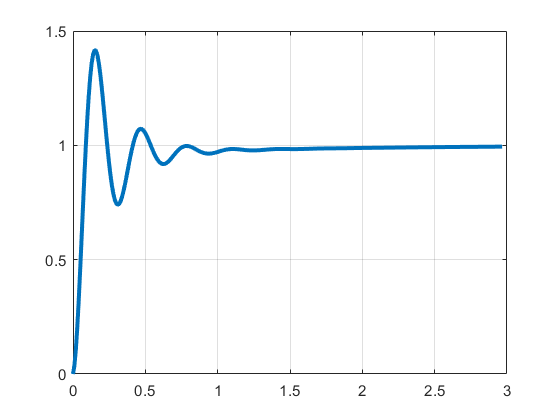

Given the system , and the gain values: . Simulate the closed-loop response of the system with the PID controller, to a step input using step().

Substitute the values into the closed-loop form and simulate.

%% PID Using Step Response

clear all;

s = tf('s');

Gp = 2 / (s^2+8*s+25);

% PID Using Step Response

% PID Gains

Kp = 200;

Ki = 150;

Kd = 1;

% System Parameters

% Initial Conditions

Gc = (Kd*s^2 + Kp*s + Ki ) / s;

Gcl = feedback(Gc*Gp, 1);

[xsteppid, tsteppid] = step(Gcl);

figure()

plot(tsteppid,xsteppid, 'LineWidth', 3)

grid on

To implement the PID Controller, or any controller, numerically, we must understand its logic in the time domain. Figure 4 shows the PID feedback controller expressed in the time domain.

The PID controller has three components: Proportional to Error, Proportional to Error Integral, Proportional to Error Derivative. So if we calculate the error, its integral and its derivative at every time sample we can compute the control law at every time sample (we assume a small enough simulation , otherwise we have to discuss digital controllers, which is outside the scope of this assignment).

EXERCISE 6

Using the provided script template, complete the algorithm definitions for

a. The first error value and first control law before the integration loop

b. The next error value in the integration loop:

c. The next error integral in the integration loop:

d. The next error derivative in the integration loop:

e. The next control output in the integration loop

From Equation 4 above.

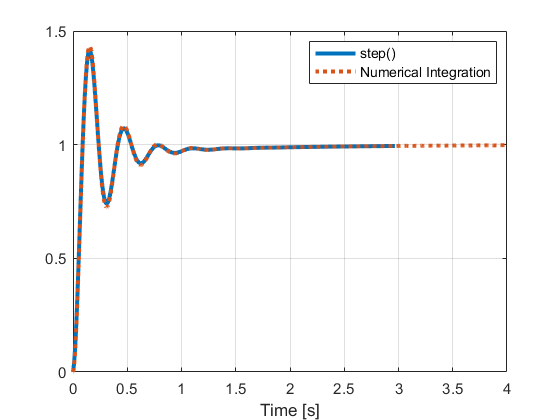

Then test your implementation of the numerical PID controller and compare the simulation output against the output you obtained using the closed-form method above. To troubleshoot your code, start first by applying the proportional gain to both methods (set , then add the integral gain (set , then add the derivative gain instead (set , then add all the gains.

%% PID Using Numerical Integration

% funtion for xdot vector - using an anonymous function. You can also

% define a separate function in a separate file or at the end of the

% script

dxdt = @(t,x,u) [x(2);

2*u - 8 * x(2) - 25 * x(1)

];

% Integration Time step

dt = 0.001;

% Time vector

t_sim = 0:dt:4;

% Initialize x

x_sim = zeros(2,length(t_sim)); % Empty 2xn array

u = zeros(1,length(t_sim)); % Empty 1xn vector

e = zeros(1,length(t_sim)); % Empty 1xn vector

e_int = zeros(1,length(t_sim));

e_dot = zeros(1,length(t_sim));

% Set Initial Conditions

x0 = [0; 0];

x_sim(:,1)= x0;

% Reference input

r = 1;

% Compute First Error

e(1,1) = 0;

% Compute First Control Output

u(1,1) = 0;

for ix = 1:length(t_sim)-1

% Simulate Response

xdot = dxdt(t_sim(ix), x_sim(:,ix), u(1,ix)); % Grab the derivative vector

x_sim(1, ix+1) = x_sim(1, ix) + xdot(1) * dt; % Integrate x1

x_sim(2, ix+1) = x_sim(2, ix) + xdot(2) * dt; % Integrate x2

% Compute Next Error

e(1, ix + 1) = r - x_sim(1, ix + 1);

% Compute Next Error Integral - Forward Integration

e_int(1, ix + 1) = e_int(1,ix) + e(1,ix) * dt;

% Compute Next Error Derivative

e_dot(1, ix + 1) = (e(1, ix + 1) - e(1, ix)) / dt;

% Compute Next Control Law

u(1,ix + 1) = Kp * e(1, ix + 1) + Ki * e_int(1, ix + 1) + Kd * e_dot(1, ix + 1);

end

figure()

plot(tsteppid,xsteppid, 'LineWidth', 3)

hold on

plot(t_sim,x_sim(1,:), ':', 'LineWidth', 3)

xlabel('Time [s]')

grid on

legend(["step()", "Numerical Integration"])

In Part I.B you retrieved the model parameters for a DCmotor, you will attempt to implement a feedback controller on this system to

a. control the speed of the motor to a given step set-point,

b. control the torque of the motor to a given step set-point.

For this question, implement the feedback controller using the transfer function method explained in Part II. Then tune the gains to achieve the required performance specifications. Plot the responses and the performance specifications.

Note: With the parameters retrieved in Part I.B. In addition, use the inductance term here to achieve a more realistic transient response, with . The transfer functions are given.

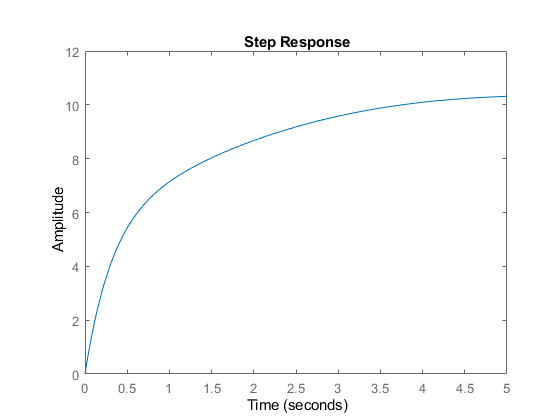

EXERCISE 7

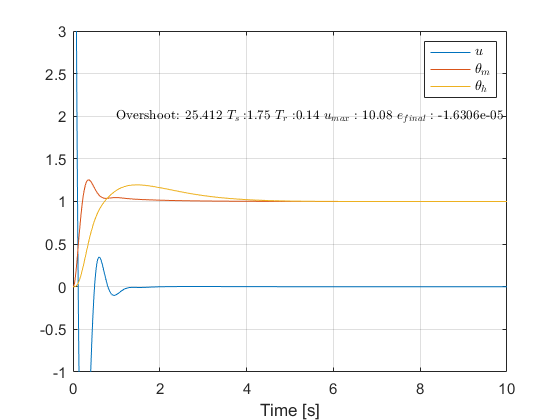

Using a PID Controller, implement it in a feedback loop to control the speed of a motor given the torque input. Attain the following performance specifications: , , , , . Plot the responses.

clear all;

Kb = 1;

Kt = 2;

Ra = 8;

J = 2;

D = 0.6;

La = 5;

s = tf('s');

G_speed = s * Kt / ( (J * s^2 + D * s) * (Ra + La * s) + Kt * Kb * s);

% Gains

Kp = 10;

Ki = 5;

Kd = 10;

% Reference Input

r = 10;

t=0:.01:5;

Gc = Kp + Ki/s + Kd * s;

s = tf('s');

Gcl_speed = feedback(Gc*G_speed,1);

E = (1 - Gcl_speed);

U_pid = Gcl_speed*E;

figure()

step(r*Gcl_speed,t)

hold on

stepinfo(r*Gcl_speed)ans =

struct with fields:

RiseTime: 2.2549

SettlingTime: 8.0145

SettlingMin: 9.0008

SettlingMax: 10.3561

Overshoot: 3.5605

Undershoot: 0

Peak: 10.3561

PeakTime: 5.7601

In class, we discussed how we can represent the transfer function relating voltage to output torque

EXERCISE 8

Use a PID controller in a feedback loop to control the Torque of the same motor. Attain the following performance specifications: , , , , . Plot the responses.

This problem should not consume much time if you have completed Part II Task 1: Use the right transfer function for the system and tune the gains through trial and error and your understanding of what each term of the PID does to achieve the required performance. Use this exercise to gain an appreciation for how each PID controller term affects the response.

G_torque = Kt * ( J * s^2 + D * s) / ( (J * s^2 + D * s) * (Ra + La * s) + Kt * Kb * s)

% Gains

Kp = 110;

Ki = 100;

Kd = 0;

% Reference Input

r = 2;

t=0:.01:2;

Gc = Kp + Ki/s + Kd * s;

s = tf('s');

% Gcl_torque = feedback(Gc*G_torque,1);

Gcl_torque = Gc*G_torque / ( 1 + Gc * G_torque);

E = (1 - Gcl_torque);

U_pid = Gcl_torque*E;

figure()

step(r*Gcl_torque,t)

hold on

stepinfo(r*Gcl_torque)G_torque =

4 s^2 + 1.2 s

-----------------------

10 s^3 + 19 s^2 + 6.8 s

Continuous-time transfer function.

ans =

struct with fields:

RiseTime: 0.0525

SettlingTime: 0.1173

SettlingMin: 1.8056

SettlingMax: 1.9786

Overshoot: 0

Undershoot: 0

Peak: 1.9786

PeakTime: 0.6789

In Part I Problem A, you were able to get a stable response for controlling the acceleration of the disk drive motor (The system is stable), if we attempt to get the speed or position response with a step input and without feedback, the system then is unstable (The systems and are unstable). We can use feedback control to stabilize the systems or .

EXERCISE 9

Use a PID Controller to achieve a stable position control response for the motor and attain the following performance specifications: , , , , .

Note: Use low values for the gains (start with values lower than 1)

Note that the input is applied on the same inertial mass we are trying to control the position of: , we can try to control directly by measuring its error instead and computing the control law output. Trying to control a part of a system (the disk drive head), while the actuation effort is at another part of the system (the motor) is termed non-collocated control, and can usually result in a nonminimum phase behavior. Trying to control an inverted pendulum's angle while applying force on the moving cart holding the pendulum, is another example of non-collocated control (it would be much easier to have a motor at the pendulum pivot: collocated control)

% PID Control structure using basic numerical integration

clear all

% PID Gains

Kp = 10;

Ki = 8;

Kd = 1;

% System Parameters

% funtion for xdot vector - using an anonymous function. You can also

% define a separate function in a separate file or at the end of the

% script

K_ = 0.07; b_ = 0.1; I_h_ = 0.04; I_m_ = 0.1;

Md = 0;

dxdt = @(t,x,u) [

x(2);

(u - K_ * x(1) - b_ * x(2) + K_ * x(3) + b_ * x(4)) / I_m_;

x(4);

(-K_ * x(3) - b_ * x(4) + K_ * x(1) + b_ * x(2)) / I_h_

];

% Integration Time step

dt = 0.01;

% Time vector

t_sim = 0:dt:10;

% Initialize x

x_sim = zeros(4,length(t_sim)); % Empty 2xn array

u = zeros(1,length(t_sim)); % Empty 1xn vector

e = zeros(1,length(t_sim)); % Empty 1xn vector

e_int = zeros(1,length(t_sim));

e_dot = zeros(1,length(t_sim));

% Initial Conditions

x0 = [0; 0; 0; 0];

x_sim(:,1)= x0;

r = 1;

% Compute First Error

e(1,1) = r - x_sim(1, 1);

u(1,1) = Kp * e(1,1) + Ki * e_int(1,1) + Kd * e_dot(1,1);

for ix = 1:length(t_sim)-1

% Simulate Response

xdot = dxdt(t_sim(ix), x_sim(:,ix), u(1,ix)); % Grab the derivative vector

x_sim(1, ix+1) = x_sim(1, ix) + xdot(1) * dt; % Integrate x1

x_sim(2, ix+1) = x_sim(2, ix) + xdot(2) * dt; % Integrate x2

x_sim(3, ix+1) = x_sim(3, ix) + xdot(3) * dt; % Integrate x3

x_sim(4, ix+1) = x_sim(4, ix) + xdot(4) * dt; % Integrate x4

% Compute Next Error

e(1, ix + 1) = r - x_sim(1, ix + 1);

% Compute Next Error Integral - Forward Integration

e_int(1, ix + 1) = e_int(1,ix) + e(1,ix) * dt;

% Compute Next Error Derivative

e_dot(1, ix + 1) = (e(1, ix + 1) - e(1, ix)) / dt;

% Compute Next Control Law

u(1,ix + 1) = Kp * e(1, ix + 1) + Ki * e_int(1, ix + 1) + Kd * e_dot(1, ix + 1);

end

% Performance Specifications

xfinal = r;

xmax = max(x_sim(1,:));

p_overshoot = (xmax / xfinal - 1) * 100;

tr0 = -1;

tr1 = -1;

ts = -1;

umax = max(u);

for ix=1:length(t_sim)

if tr0 == -1 && x_sim(1,ix) > 0.1 * xfinal

tr0 = t_sim(ix);

end

if tr1 == -1 && x_sim(1,ix) > 0.9 * xfinal

tr1 = t_sim(ix);

end

if ts ~= -1 && abs(x_sim(1,ix) - xfinal) > 0.02 * xfinal

ts = -1;

end

if ts == -1 && abs(x_sim(1,ix) - xfinal) < 0.02 * xfinal

ts = t_sim(ix);

end

end

tr = tr1 - tr0;

txt = ['Overshoot: ' num2str(p_overshoot) ' $T_s: $' num2str(ts) ' $T_r: $' num2str(tr) ' $u_{max}:$ ' num2str(umax) ' $e_{final}:$ ' num2str(e(1,end))];

% And plot

figure()

plot(t_sim,u(1,:)); hold on; grid on

plot(t_sim,x_sim(1,:))

plot(t_sim,x_sim(3,:))

ylim([-1,3])

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('$u$','$\theta_m$','$\theta_h$', 'Interpreter','latex')

text(1,2,txt,'Interpreter','latex')

Bonus Task: Instead of applying the PID on the motor angular position, try to apply it on the drive read head , try to come up with a stable response. Try to get the following performance specifications: , , , , .

You will notice that with only PID control, we are better off implementing a collocated controller. There are more advanced ways of controlling non-collocated systems, which is the subject of another course.